It has been said that what we learn from history is that we don’t learn anything at all from history. I believe that a little bit of history will help us understand the current global economic crisis. German’s inflation was triggered by a huge increase in the money supply because of the heavy reparations assigned to Germany after losing World War I.

It has been said that what we learn from history is that we don’t learn anything at all from history. I believe that a little bit of history will help us understand the current global economic crisis. German’s inflation was triggered by a huge increase in the money supply because of the heavy reparations assigned to Germany after losing World War I.

Before World War I Germany was a prosperous country, a prosperous economy, and a world leader in chemical, optics, and machinery. In 1914 the German mark, the British shilling (which was a former monetary unit in Great Britain), the French franc, and the Italian lira all had equal value, and were all exchanged four or five to the dollar.

By 1923, however, the exchange rate between the dollar and the mark was one trillion marks to one dollar. The German government chose to pay its debts with cheap marks, printing as many as needed to stem the crisis. When the initial injections of newly printed money failed to work, the government’s response was the same: print more money.

The prices of goods rose every day as tax revenues collapsed and the government-financed all its activities through the printing of money. With all this quantitative easing, the economy seemed to be working very well and unemployment was low. But remember that printing money is similar to an addiction to drugs. Once you start printing, it is very hard to ever stop. German currency was relatively stable at about sixty marks per the United States dollar during the first half of 1921.

The rise in prices hit the middle class and those on fixed incomes hard. People who had fixed incomes were wiped out and many who had saved money found that their savings were worthless and all retirement funds were reduced to nothing. At the retail level, it was only barter trade that had become the main means of exchange when currencies had collapsed completely as a result of hyperinflation.

In such desperate times when money is useless, whatever could be bartered was used in exchange for food or clothes. By late 1922 inflation was out of control. There was widespread corruption; prostitution, riots, political assassinations, and crime— social upheavals became common.

The only ones who benefited were those with foreign bank accounts, farmers, landowners, and those with big mortgages. They were glad when the purchasing power of the mark fell so that they could repay their loans with worthless pieces of paper. As a matter of fact, big corporations urged the government into deliberately letting the mark fall in order to free the government of its public commitments and help businesses that needed to cancel their large debts.

For example, great German industrial corporations like Krupp, Thyssen, Farben, and Stinnes reasoned they would make German goods cheap and easy to export, and they needed the export earnings to buy raw materials abroad.

Inflation kept everyone working. Next, the masses who depended on fixed incomes, pensions, and savings greatly suffered. The professionals-engineers, lawyers, architects, surveyors, scientists, and others could not find any demand for their services.

The currency lost meaning and the people lost faith in the financial system. When the thousand billion mark note was printed, few bothered to collect the change when they spent it. American writer Pearl Buck was living in Germany in 1923. She later wrote:

The cities were still there, the houses not yet bombed and in ruins, but the victims were millions of people. They had lost their fortunes, their savings; they were dazed and inflation-shocked and did not understand how it had happened to them and who the foe was who had defeated them. Yet they had lost their self-assurance, their feeling that they themselves could be the masters of their own lives if only they worked hard enough; and lost, too, were the old values of morals, of ethics, of decency.

Due to the economic crisis in Germany, there was no gold available to back the currency. Therefore, the Rentenmark was introduced which brought an end to hyperinflation. Adam Fergusson describes what happened next:

The post-hyperinflationary credit crunch was, not surprisingly followed by a credit boom: starved of money and basic necessities for so long (do not forget the hyperinflation had come directly after defeat in the Great War), many funded lavish lifestyles through borrowing during the second half of the 1920s. We know how that ended, of course: in The Great Depression, which eventually saw the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the National Socialist era.

The companies in Germany went bankrupt and workers were laid off. By the end of 1930 unemployment affected most German families just six years after the last hyperinflation had hit the Weimar Republic. By the end of 1932, over 30 percent of all German workers were unemployed.

Most of those who were unemployed were family men who could not provide for their families. Deprived of jobs and decent living, the Germans were willing to do anything to survive.

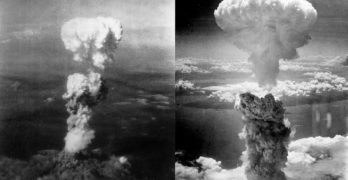

Those who saw no end to their troubles turned to the more extreme political parties in Germany— the Nazi and Communist parties. Hitler’s Rise to Power. We all know the term “never let any crisis go to waste” because in such an economic crisis a leader who wants to capture a nation will be waiting to take advantage of the situation.

On January 30, 1933, Hitler was sworn in as chancellor. He had waited for this opportunity after his attempted coup had failed in 1923. But thanks to democracy, the Nazi party legally won thirty-two seats in the next elections and the National Democratic Party won 106. Within one month after the elections, Hitler was on his way to become a dictator, and the rest is history.

Politicians know that many people would be willing to sell their souls if they could be assured of jobs. Dr. Lutzer has said,

Given a choice, many of us would prefer economic equality along with tyranny rather than economic opportunity with freedom, most will choose bread and sausage above individual liberties.

Historian David A. Rausch describes how Hitler’s brand of socialism had many advantages for the German people:

Hitler had lowered wages; state governments and economies were consolidated under the totalitarian regime; and Germany began to rearm. The economy began to recover and men were put back to work but at the high price of personal freedom. Virtually every area of German life was under the control of the Nazi regime, yet more citizens did not seem to care. Fed a steady dosage of propaganda by the press and entertained with massive rallies, parades, and “gifts” from “The Führer,” the German people swelled with pride at their nation’s apparent comeback.

According to Dr. Lutzer, one of the most important lessons to learn from this part of history is that:

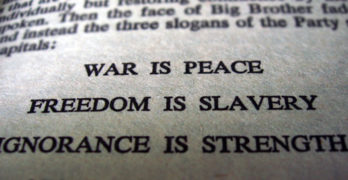

Some politicians often use an economic and political crisis to make their subjects more government dependent, and with that dependency comes more control…. With expanded government control comes loss of religious liberty and loss of the work ethic. This was most clearly seen in communist countries where wages were set by the government and doled out by the government. For the politicians to control the state coffers is of great benefit to them, because the more people are dependent on the government for their existence, the more willing they are to bow to whatever the government demands.

The goal of those in power has always been to level everyone and make us all equally poor. Why? Because power and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Another example that has been widely circulated on the Internet was given by an elderly woman named Kitty Werthmann. She told audiences what life was like in Austria during the late 1930s:

In 1938, Austria was in deep Depression. Nearly one-third of our workforce was unemployed. We had 25 percent inflation and 25 percent bank loan interest rates…. Farmers and business people were declaring bankruptcy daily. Young people were going from house to house begging for food. Not that they didn’t want to work; there simply weren’t any jobs…. The Austrian people were really hurting and they were desperate for answers. When Hitler came to them with “solutions,” they were ready to embrace him with open arms….

We looked to our neighbor on the north, Germany, where Hitler had been in power since 1933. We had been told that they didn’t have unemployment or crime, and they had a high standard of living. Nothing was ever said about persecution of any group— Jewish or otherwise. We were led to believe that everyone in Germany was happy.

We wanted the same way of life in Austria. We were promised that a vote for Hitler would mean the end of unemployment and help for the family. Hitler also said that businesses would be assisted, and farmers would get their farms back. Ninety-eight percent of the population voted to annex Austria to Germany and have Hitler for our ruler. We were overjoyed and for three days we danced in the streets and had candlelight parades. The new government opened up big field kitchens and everyone was fed.

Prices Controlled By the Führer

Economist Ludwig von Mises’s analysis of the situation in both Germany and England at that time was that both countries experienced inflation. Prices went up, and the two governments imposed price controls. Starting with a few prices, with only milk and eggs, they had to go up further and further.

The longer the war went on, the more inflation was generated. After three years of war, the Germans elaborated on a great plan. They called it the Hindenburg Plan, which meant that the government would control the whole German economic system: prices, wages, profit— everything.

And the bureaucracy immediately began to put this into effect. But before they finished, the debacle came: the German Empire broke down, the entire bureaucratic apparatus disappeared, the revolution brought its bloody results, and things came to an end.

In England, they started in the same way, but after a time, in the spring of 1917, the United States entered the war and supplied the British with sufficient quantities of everything they needed. Therefore the road to socialism and serfdom was interrupted.

Before Hitler came to power, Chancellor Bruning again introduced price control in Germany for the usual reasons. And Hitler enforced it even before the war started. For in Hitler’s Germany there was no private enterprise or private initiative; there was only a system of socialism which differed from the Russian system only to the extent that the terminology and labels of the free economic system were still retained.

There still existed “private enterprises,” as they were called. But the owner was no longer an entrepreneur; rather, the owner was called a “a shop manager.” The whole of Germany was organized in a hierarchy of führers— there was the Highest Führer, Hitler of course, and then there were führers down to the many hierarchies of smaller führers. And the head of an enterprise was the betriebsfuhrer— the workers of the enterprise were named by a word that, in the Middle Ages, had signified the retinue of a feudal lord: the gefolgschaft.

And all of these people had to obey the orders issued by an institution which had a terribly long name, Reichfuhrerwirtschaftsministerium, at the head of which was the well-known fat man named Goering, adorned with jewelry and medals. And from this body of ministers came all the orders to every enterprise: what to produce, in what quantity, where to get the raw materials, and what to pay for them, to whom to sell the products and at what prices to sell them.

The workers got the order to work in a definite factory, and they received wages that were decreed by the government. The whole economic system was now regulated in every detail by the government. The betriebsfuhrer did not have the right to take the profits for himself; he received only what amounted to a salary. If he wanted to get more he would say, for example, “I am very sick, I need an operation immediately, and the operation will cost five hundred marks.”

Then he had to ask the führer of the district (the gaufuhrer or gauleiter) whether he had the right to take out more than the salary given to him. The prices were no longer prices and the wages were no longer wages— they were all quantitative terms in a system of socialism.

The system of the German Nazis retained the labels and terms of the capitalistic free market economy. But they meant something very different: there were now only government decrees. The question is, How did the church respond? This will be covered in Part 2 and 3.