William Wilberforce was an evangelical Christian and a Member of Parliament for Yorkshire (1784–1812). He came to faith in Jesus Christ in 1785 at the age of twenty-five, and he almost missed his high calling. His first reaction after being converted was to give up politics and join the ministry. He thought, as millions have thought before and since that time, that spiritual affairs are far more important than secular ones.

William Wilberforce was an evangelical Christian and a Member of Parliament for Yorkshire (1784–1812). He came to faith in Jesus Christ in 1785 at the age of twenty-five, and he almost missed his high calling. His first reaction after being converted was to give up politics and join the ministry. He thought, as millions have thought before and since that time, that spiritual affairs are far more important than secular ones.

Fortunately, John Newton, the converted slave trader who wrote “Amazing Grace,” persuaded Wilberforce that God wanted him to stay in politics rather than enter the ministry.

He was counseled by John Newton to follow Christ but not to abandon public office. “It’s hoped and believed,” Newton wrote, “the Lord has raised you up to the good of His church and for the good of the nation. Yes, I trust that the Lord, by raising up such an incontestable witness to the truth and power of the gospel, has a gracious purpose to honor Him as an instrument of reviving and strengthening the sense of real religion where it is already, and of communicating it where it is not.”

This motivated Wilberforce to think about his conversion and calling. Did God call him to just rescue his own soul from hell? He could not accept that as God’s sole purpose for him. If Christianity was true and meaningful, it must not only save but also serve. It must bring God’s compassion to the oppressed as well as oppose the oppressors.

The Bible says, “Learn to do right! Seek justice, relieve the oppressed, and correct the oppressor. Defend the fatherless, plead for the widow” (Isaiah 1:17 AMP).

After much prayer and thought, Wilberforce concluded that Newton was right. God was calling him to champion the liberty of the oppressed as a Parliamentarian. “My walk,” he wrote in his journal in 1787, “is a public one. My business is in the world; and I must mix in the assemblies of men, or quit the post which Providence seems to have assigned me.”

That was a key moment in British and world history. A few months later, on Sunday, October 28, 1787, he wrote in his journal the words that have become famous: “God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners—in modern terms, ‘habits, attitudes, morals.’” No greater reformer in Western history is so little known as William Wilberforce.

His success in the first of the “two great objects” was described by a Wilberforce biographer, John Pollock, as “the greatest moral achievement of the British people” and by historian G. M. Trevelyan as “one of the turning events in the history of the world.” Another historian credited his success with saving England from the French Revolution and demonstrating the character that was to be the foundation of the Victorian age.

An Italian diplomat who saw Wilberforce in Parliament in his later years recorded that “everyone contemplates this little old man…as the Washington of humanity.”

John Pollock gave a fascinating lecture on Wilberforce at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 1996. Among his comments were:

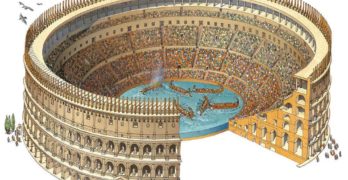

One evening a young English MP pored over papers by candlelight in his home beside the Houses of Parliament. Wilberforce had been asked to propose the Abolition of the Slave Trade although almost all Englishmen thought the trade necessary, if nasty, and that economic ruin would follow if stopped. Only a very few thought that Slave Trade was wrong and evil. Wilberforce’s research pressed him to excruciatingly clear conclusions. “So enormous, so dreadful,” he told the House of Commons later, “so irremediable did the Trade’s wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for Abolition. Let the consequences be what they would, I would from this time determine that I would never rest until I had effected its abolition.

Wilberforce’s accomplishments were achieved against all odds. He was a little man with a relatively weak physical makeup with a faith that was despised. His task was almost impossible because the practice of slavery was almost universally accepted and the slave trade was as important to the economy of the British Empire as the defense industry is to the United States today.

His opposition included powerful mercantile and colonial vested interests, such as national heroes as Admiral Lord Nelson, and most of the royal family. As regards to his perseverance, Wilberforce tirelessly kept on for nearly fifty years before he accomplished his goal. He was constantly mocked, ridiculed, and vilified; he was twice waylaid and physically assaulted. He was criticized by slave-defending adversaries who claimed that Wilberforce pretended to care for slaves from Africa but cared nothing about “the wage slaves”—the wretched poor of England.

Encouragement from John Newton and John Wesley

At one point Wilberforce became discouraged after, unexpectedly, his motion to abolish the slave trade on January 1, 1796, was defeated in Parliament by seventeen votes. He was devastated by this setback and thought of giving up his campaign for the abolishment of slavery. He received a letter from Newton, reminding him of the sovereignty of God in the midst his circumstances:

You’ve acted nobly, Sir, in behalf of poor Africans. I trust you will not lose your reward. But I believe the business is now transferred to a higher hand. If men will not redress their accumulated injuries, I believe the Lord will. I shall not wonder if the Negative lately put upon your motion should prove a prelude to the loss of all our West India Islands…. But I would leave a more favorable impression upon your mind before I conclude. The Lord reigns. He has all hearts in His hands. He is carrying on His great designs in a straight line, and nothing can obstruct them.

Newton kept assuring Wilberforce that God had raised him up to be His chosen servant in British public life. Another trying moment for Wilberforce came when he fell ill in the spring of 1788. The doctors thought he was going to die, but Newton was confident about his recovery. When Newton heard the good news that his friend had somehow recovered, he wrote to him:

When you were at the lowest, my hopes were stronger than my fears. The desires and opportunities the Lord has given you, of seeking to promote the political, moral, and religious welfare of the kingdom, has given me a pleasing persuasion that he has raised you up and preserved you to be a blessing to the public. I humbly and cheerfully expect that you will come out of the furnace refined like gold.

The most important correspondence came in July of 1796, however, when Wilberforce wrote to Newton saying that he was considering retirement from public life. Newton once again strongly opposed Wilberforce’s urge to end his political career. He wrote back to him on July 21, 1796, to say that his reelection as MP for Hull was a sign that God had further work for him to do:

If after taking the proper steps to secure your continuance in Parliament you had been excluded, it would not have greatly grieved you. You would have looked to a higher hand and considered it as a providential intimation that the Lord had no further occasion for you there. And in this view I think you have received your dismissal with thankfulness. But I hope it is a token for good that He has not yet dismissed you.

John Wesley, who was on his deathbed, also heard about Wilberforce desiring to give up. He asked for a pen and paper and wrote Wilberforce the following letter:

Dear Sir, Unless the divine power has raised you as Athanasius contra mundum, I see not how you can go through your glorious enterprise in opposing that execrable villainy which is the scandal of religion, of England, and of human nature. Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you? Are all of them together stronger than God? Oh, be not weary of well-doing! Go on, in the name of God and in the power of His might, till even American slavery (the vilest that ever saw the sun) shall vanish away before it.

Reading this morning a tract wrote a poor African, I was particularly struck by that circumstance that a man who has a black skin, being wronged or outraged by a white man, can have no redress; it being a “law” in our colonies that the oath of a black against a white goes for nothing. What villainy is this? That He who has guided you from youth up may continue to strengthen you in this and all things, is the prayer of, dear sir.

Wesley died six days later (in 1791). Wilberforce took his words of encouragement to heart and persisted with his crusade. Another friend once wrote to him cheerfully: “I shall expect to read of you carbonadoed by West Indian planters, barbecued by African merchants and eaten by Guinea captains, but do not be daunted, for I will write your epitaph!”

Newton was sympathetic with Wilberforce’s inclination to enjoy a private life and avoid many things that wearied and disgusted him. But he continued reminding him of his duty to promote the cause of God and public good:

Nor is it possible at present to calculate all the advantages that may result from your having a seat in the House at such a time as this. The example and even the presence of a consistent character may have a powerful though unobserved effect upon others. You are not only a representative for Yorkshire, you have the far greater honor of being a representative for the Lord in a place where many know Him not, and an opportunity of showing them what are genuine fruits of that religion that you are known to profess.

Newton’s final appeal in his letter was based on a comparison between Wilberforce and Daniel:

You live in the midst of difficulties and snares, and you need a double guard of watchfulness and prayer. But since you know both your need of help and where to look for it, I may say to you as Darius to Daniel, “Thy God whom thou servest continually is able to preserve and deliver you.” Daniel likewise was a public man and in critical circumstance. But he trusted in the Lord, was faithful in his departments, and therefore though he had enemies they could not prevail against him.

Another final correspondence worth mentioning was Newton’s constant encouragement of Wilberforce by the prayers and benedictions with which many of his letters ended. Among them was this:

May the Lord bless and guard you, My Dear Sir, and make you yourself as a watered garden and in all your connections as a spring whose waters fail not. My prayers are particularly engaged for you that the Lord may furnish you with wisdom, grace, and strength every way equal to the importance and difficulty of your situation. May the Lord comfort you in the midst of your labors, give you the desire of your heart in promoting the good of others, and fill your soul with His wisdom, grace and consolation. My heart is often with you, and my poor prayers are often engaged for you. That the Lord may give you a double portion of His Spirit to improve the advantages and to obviate the difficulties of your situation. That you may be happy in His peace yourself and that your influence may by His blessing promote the happiness and welfare of many.

Wilberforce’s Determination

William Wilberforce’s faith in Jesus Christ animated his lifelong passion for reform. He was convinced that Almighty God had set before him two great objectives, “the abolition of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.” As Charles Colson wrote in the Preface to A Practical View of Christianity:

The opposition to end slavery was equally determined not to vote for its end, pointing to the jobs and exports that would be lost. Wilberforce again filled the House of Commons with stirring eloquence: “Never, never will we desist till…we extinguish every trace of this bloody traffic.”

When the abolitionists analyzed their battle in 1792, they were painfully aware that many of their colleagues were puppets, unable or unwilling to stand against the powerful economic forces of their day. So Wilberforce and his friends decided to go to the people, believing, “It is on the general impression and feeling of the nation we might rely…so let the flame be fanned.” The abolitionists distributed thousands of pamphlets detailing the evils of slavery, spoke at public meetings, and circulated petitions.

Thousands of British subjects signed the petition for the total abolition of the slave trade, making a huge difference in swaying the tide. For several years, Wilberforce introduced the motion for abolition; and each year Parliament threw it out. And so it went—1797, 1798, 1799, 1800, and 1801—the years passed with Wilberforce’s motions thwarted and sabotaged by political pressures, compromise, his illness, and the war in France.

Finally, by God’s grace in 1806, Wilberforce’s efforts began to show some light at the end of the tunnel. His friend William Pitt, who had become prime minister in 1784 at the tender age of twenty-four, died on January 23, 1806, and William Grenville, a strong abolitionist became prime minister in his place. He reversed the pattern of the previous twenty years, and introduced Wilberforce’s bill into the House of Lords.

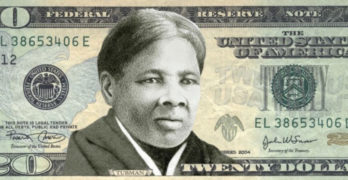

In 1807, sixteen years after he had begun, Wilberforce succeeded in getting the English slave trade abolished. It took another twenty-six years for him to achieve the abolition of slavery in England altogether. The bill was passed in 1833, which was the year Wilberforce died, at age seventy-four.

Spiritual Movement

In the years that followed, a great spiritual movement swept across England. With the outlawing of the slave trade came Wilberforce’s eighteen-year battle toward the total emancipation of the slaves. Social reforms swept beyond abolition to clean up child labor laws, poorhouses, and prisons, and to institute education and healthcare for the poor. Evangelism flourished, and later in the century missionary movements sent Christians around the world.

This was a result of a rich Christian biblical heritage in the public square. Though some people are accusing Christians of imposing their personal religious views on others, again we ought to remember that in America and Great Britain it was the Christians who led the fight against slavery, enacted child labor laws, opened hospitals, and ran charitable societies to aid widows, orphans, alcoholics, and prostitutes.

And it is the Christians who are acting as salt and light in society today. Wilberforce knew this quite well. He wrote in A Practical View of Christianity:

I must confess equally boldly that my own solid hopes for the well being of my country depend, not so much on her navies and armies, nor on the wisdom of her rulers, nor on the spirit of her people, as on the persuasion that she still contains many who love and obey the Gospel of Christ. I believe that their prayers may yet prevail.

Today world leaders are debating how to handle the host of social challenges and human crises, but one person looked beyond selfish interests and fought for the abolition of the African slave trade in the various British colonies until they were illegal in the whole of the British Empire.

He truly lived out his convictions not only by working to abolish slavery but by reforming other social injustices that still influence our national values today. His tireless efforts, life, and faith in the Lord Jesus Christ serve as an inspiration and example to all disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Recommended Reading:

- George Macaulay Trevelyan, British History of the Nineteenth Century (1782–1901) (Longmans Green and Company: New York, 1922).

- Os Guinness, Character Counts: Leadership Qualities in Washington, Wilberforce, Lincoln, and Solzhenitsyn, (Baker Books: Michigan, 1999).

- Betty Steele Everett, Freedom Fighter: The Story of William Wilberforce (Fort Washington, PA: Christian Literature Crusade, 1994).

- John Piper, Amazing Grace in the Life of William Wilberforce (Wheaton: Crossway Books, 2006).

- John Pollock, Wilberforce “A Man Who Changed His Times,” (London: Constable and Company, 1977).

- Robert K. Ssebatta, Reclaiming the Forgotten Biblical Heritage: When a People Forget Their Heritage, They Are Easily Persuaded to Lose Their Identity (Watchman Media Publications 2014).

- William Wilberforce, A Practical View of Christianity (Hendrickson Publishers) Peabody, Massachusetts, 1996).