Lessons From The East African Revival Fellowship-Part 3

The East African Revival Fellowship, as it came to be known, was as controversial as it was transformative for those who became saved through the message that came from the lips of those who preached Christ, His death and resurrection. Therefore, before we look at the controversies surrounding how it ended, we need to briefly establish how Christianity arrived in Uganda.

The East African Revival Fellowship, as it came to be known, was as controversial as it was transformative for those who became saved through the message that came from the lips of those who preached Christ, His death and resurrection. Therefore, before we look at the controversies surrounding how it ended, we need to briefly establish how Christianity arrived in Uganda.

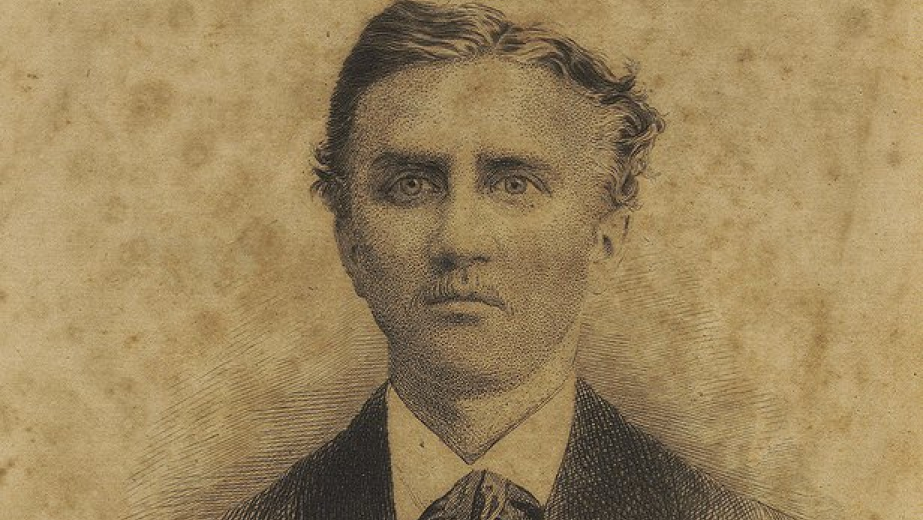

Christianity came to Uganda in 1877 through the dedicated efforts of Alexander Mackay (1849–1890), a Scottish Presbyterian missionary and trained engineer. He has been called a pioneer-missionary to Uganda, which was described by explorer Henry Stanley as the “Pearl of Africa.” He arrived in Zanzibar in 1876 and reached Uganda in 1878.

The Missionary and Engineer

Mackay firmly believed in the church’s missionary mandate and came to Uganda not only to preach but to share his professional skills. The people he evangelised he also taught to make roads and build bridges, to read, write, use the printing press and to use modern methods of cultivation. He built 230 miles of road to Uganda from the coast, and translated the Gospel of Matthew into Luganda.

He was assisted by James Hannington, the first Bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa. After many years of devotion to the Master’s cause in Africa, he conceived the idea of pushing right into the heart of Uganda for the purpose of communicating with, and assisting Mackay, who in spite of terrible persecution, persisted in delivering his God given message. Hannington’s last heroic words were:

Tell the king that I will die for Uganda. I have bought this road with my life.

Mackay’s favorite Bible character was John the Baptist, and he cited Matthew 3:3 and other passages that describe John the Baptist’s commission to prepare the way for the coming of the Savior. He told King Mutesa I, who reigned from 1856–1884 that:

When in ancient days, the people failed to keep the commandments of God and continued in their sinful ways, God determined to send His only Son to earth to redeem sinners and sent John the Baptist to prepare the people for His coming. I am here, O king, to prepare a way for the coming of God’s Son and I want you to join me in pointing the people of this land to the Lamb of God, who alone can take away the sin of the world.

Mackay wasn’t the only person who appeared before the king and his chiefs. It is been recorded by one historian that walked into the king’s chamber was a tall Arab in flowing robes and a red fez, followed by a number of black men, who deposited on the floor their bales of cloth and guns:

I have come to exchange these things for men, women and children. I will give you one of these links of red cloth for one man, one of these guns for two men and one hundred of these percussion caps for one woman.

Mackay’s Encounter with King Mutesa

Mackay knew that the king was accustomed to selling his own people, as well as his captives, as slaves. He could see that the king was especially eager to get guns and ammunition, for they would enable him to conquer and enslave his enemies. Now the question on Mackay’s mind was: Should I risk the king’s disfavor, and even risk my own life, by opposing this traffic in human lives? He remembered that, though it cost him his head, John the Baptist did not hesitate to reprove a king by speaking what was right. Inspired by this courageous example, Mackay declared:

O king Mutesa, the people of this land made you their king and look to you as their father. Will you sell your children, knowing that they will be chained, put into slave-sticks, beaten with whips; that most of them will die of mistreatment on the way and the rest be taken as slaves to some strange country? Can you be a party to these crimes, even for the sake of some guns? Will you sell scores or hundreds of your people, or your captives, whose bodies are so marvelously created by God, for a few bolts of red cloth which any man can make in a few days?

The Arab slave dealer scowled. If only he could plunge his dagger into the white man’s heart! No man had ever dared talk to the king like this before, and the chiefs stirred uneasily, wondering if Mutesa would imprison Mackay or perhaps put him to death. Instead, he dismissed the angry Arab and announced:

The white man is right. I shall no more sell my people as slaves.

With a joyful and grateful heart, the missionary went to his hut. Later the same day he wrote in his diary: “Afternoon. The king sent a message with a present of a goat, saying it was a blessed passage I read today.”

His Professional Background

Mackay showed unusual interest in mechanics ever since he was a small boy. At one time, he walked back eight miles in order to look at a railway engine for at least two and a half minutes. He also liked to linger around the blacksmith’s shop and the carding mill, and spent considerable time in the attic at his little printing press.

Thirteen years went by, during which he completed a two years’ teaching course, learned much about shipbuilding in the docks of Aberdeen, made a thorough study of engineering, and went to Germany for further study. He had read avidly all he could find about his hero, David Livingstone, and on the anniversary of Livingstone’s death, he wrote in his diary:

Livingstone died—a Scotsman and a Christian—loving God and his neighbour, in the heart of Africa. Go thou and do likewise.

But how could he ever go to Africa? What could an engineer do there? As he was pondering these questions in Berlin on the night of December 12, 1875, he picked up a copy of the Edinburg Daily Review which was sent to him from Scotland.

He read a letter that sent a mighty chill through his being. Because of its author, the place of its composition, the story of its transmission, its contents, and its consequences, this was one of the most remarkable letters ever penned. It was written by the explorer Henry M. Stanley, in Uganda on April 12, 1875, at the request of King Mutesa.

More than seven months transpired before it appeared in the Daily Telegraph of London and in all other papers. It is the story of a pair of boots, owned and worn by a Frenchman, Colonel Linant de Balleonds, to whom Stanley entrusted the letter. Marching northward from Uganda, the Frenchman and his caravan were proceeding along the bank of the River Nile when they were suddenly attacked near Gondokoro by a band of savage tribesmen.

Having killed the Frenchman, they heartlessly left his body lying unburied on the sand, where it was later discovered by some English soldiers who happened to pass that way. Before burying the Frenchman, they pulled off his long knee boots and in one of them found Stanley’s letter, stained with the dead man’s blood.

They forwarded it to the English general in Egypt, who sent it on the newspaper office in London. This was the letter which attracted Mackay’s attention that cold December night in 1875. In part it read as follows:

King Mutesa of Uganda has been asking me about the white man’s God…. Oh that some practical missionary would come here! Mutesa would welcome such. It is the practical Christian who can cure their diseases, build dwellings and turn his hand to anything—this is the man who is wanted. Such a one, if he can be found, would become the savior of Africa.

Having long cherished a desire to follow in the footsteps of Livingstone and Stanley, this was for him a call from on high. Immediately he wrote to the CMS (Church Missionary Society):

My heart burns for the deliverance of Africa, and if you can send me to any of those regions which Livingstone and Stanley have found to be groaning under the curse of the slave hunter, I shall be very glad.

Within four months Mackay, along with seven other young missionary volunteers, was on a ship bound for Zanzibar and Uganda, saying: “I go to prepare the way by which others more readily can go and stay and work.”

The Concept of Discipleship

His understanding of the gospel was deep and his preaching was simple. He emphasized repentance, conversion and the ongoing confession of sins. Without ongoing confession, Mackay told the new converts, the church would lose its power and the people of God would lose their joy.

As Mackay travelled throughout Uganda, he longed for the day when Ugandan Christians would cease to think of Christianity as a white man’s religion. Wherever he established a new church, he emphasized the importance of local leadership. He trained tribal chiefs and entrusted to them the responsibility of discipling their own people.

He used their homes as temporary mission stations. By the time he was ready to leave a village for another missionary journey, it was the tribal chief and not Alexander Mackay who had become the spiritual leader of the people.

Mackay died in 1890 after spending fourteen years in Africa without once returning home to his native Scotland. He had given his best, his all, to the high task of being a road maker for Christ in the heart of Africa.

His vision of a strong national church became a reality in his own lifetime. With barely a handful of missionaries in the country the number of native evangelists increased steadily. By the end of the century more than 260 evangelists were preaching the gospel and eight-five mission stations had been established.

Whatever the original motivation of Mackay and other missionaries, the pervasiveness of Western influence had alienated some Christian believers from the church. Many Christians were convinced that foreign intervention might be the only long-term solution to safeguard the future of Christianity in Buganda and subsequently the whole nation.

Ultimately, there was more resistance, especially as the believers often conflicted with resurgent Buganda nationalists who were seeking consciously to indigenize their worship. I believe the end of the East African Revival Fellowship particularly, in Uganda had a lot to do with the continuance of deeply held traditional cultural practices. The Lord willing, those are some of the lessons we shall examine in Part 4.