Slavery is a State of Mind

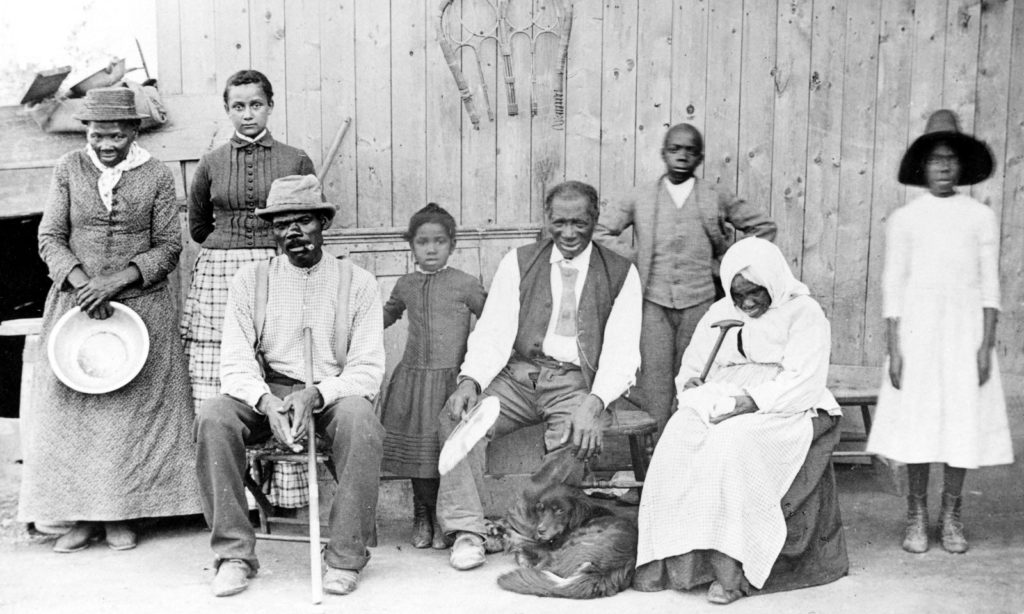

Tubman in 1887 (far left), with her husband Davis (seated, with cane), their adopted daughter Gertie (beside Tubman), Lee Cheney, John “Pop” Alexander, Walter Green, Blind “Aunty” Sarah Parker, and great-niece, Dora Stewart at Tubman’s home in Auburn, New York. Source: Wikipedia

Tubman in 1887 (far left), with her husband Davis (seated, with cane), their adopted daughter Gertie (beside Tubman), Lee Cheney, John “Pop” Alexander, Walter Green, Blind “Aunty” Sarah Parker, and great-niece, Dora Stewart at Tubman’s home in Auburn, New York. Source: Wikipedia

Harriet Tubman (1820–1913), known for her role in leading dozens of slaves out of the South to freedom, succeeded in her work through trust in the Lord and a steadfast life of prayer.

She was born into slavery in Maryland in the early 1820s, and was christened Araminta Ross by her parents, Harriet and Benjamin Ross, but later decided to go by her mother’s first name. Her time as a slave was spent being hired out to do housework and later, physical labor outdoors. At fourteen, during an attempt to protect a slave who was running from his master, she was hit in the head by a large weight. She nearly died, and her recovery took months.

The resulting concussion caused Harriet to experience sudden sleeping spells for the rest of her life, but it may have also been the beginning of a deepening relationship with God. She “began having visions and speaking with God on a [regular] basis, as directly and pragmatically as if he were a guardian uncle whispering instructions exclusively to her and in the most concrete terms about what to do and not do, where to go and not go.”

Harriet had a dream in her heart: to be free from slavery. At age twenty-four she married John Tubman, a free black man, in 1844, but it wasn’t until 1849 that she felt the time was right to escape. But when she talked to her husband about escaping to freedom in the North, he wouldn’t hear of it.

He said that if she tried to leave, he’d turn her in. When she resolved to take her chances and go forth in 1849, she did so alone, without a word to him. Her first biographer, Sarah Bradford, said that Tubman told her:

I had reasoned this out in my mind: there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death. If I could not have one, I would have the other, for no man should take me alive. I should fight for my liberty as my strength lasted, and when the time came for to go, the Lord would let them take me…..When I think of all the groans and tears and prayers I’ve heard on plantations, and remember that God is a prayer-hearing God, I feel that his time is drawing near. He gave me my strength, and he set the North Star in the heavens; He meant I should be free.”

With the help of the Underground Railroad, she was able to make her way to Philadelphia and freedom. However, Harriet was not content to enjoy her freedom on her own and longed for others to be free as well. We need to be reminded that the slaves in America or Britain did not win their freedom, but it was bestowed to them by the government. As a result, this freedom did not bring true closure and fulfillment. Harriet Tubman knew that very few people would be willing to fight and die for this freedom.

She was fearless, and her leadership was unshakable. Hers was extremely dangerous work, and when people in her charge wavered or had second thoughts, she was strong as steel. Tubman knew escaped slaves who returned would be beaten and tortured until they gave information about those who had helped them. So she never allowed any people she was guiding to give up. “Dead folks tell no tales,” She would tell a fainthearted slave as she put a loaded pistol to his head. “You go on or die.”

After reaching Philadelphia, in 1850, she made the first of what would be approximately thirteen trips back into slave territory for the purpose of guiding others to freedom.

Harriet felt like her role in the Underground Railroad was a commandment she had been given from God. “The Lord told me to do this. I said, ‘Oh Lord, I can’t—don’t ask me—take somebody else.’” But Harriet also reported that God spoke directly to her: “It’s you I want, Harriet Tubman.”

For ten years Harriet would work tirelessly as a guide, helping around seventy people, including her own mother and father, make it to freedom. When rescuing her family she said,

I was a stranger in a strange land my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were [in Maryland]. But I was free, and they should be free.

Because the Fugitive Slave Law had made the northern United States more dangerous for escaped slaves, many began migrating to Southern Ontario. In December 1851, Tubman guided an unidentified group of 11 fugitives, possibly including the Bowleys and several others she had helped rescue earlier, northward. In his third autobiography, Abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass wrote:

On one occasion I had eleven fugitives at the same time under my roof, and it was necessary for them to remain with me until I could collect sufficient money to get them on to Canada. It was the largest number I ever had at any one time, and I had some difficulty in providing so many with food and shelter….The number of travellers and the time of the visit makes it likely that this was Tubman’s group.

As Harriet would recount stories of rescue after rescue, stories filled with suspense and danger, it would become evident that the closeness of her friendship with God was a primary theme. He protected her and she trusted Him implicitly. Harriet’s testimony of God’s care for her was that she would only go where He sent her and that He would keep her safe throughout her journeys.

Harriet continued to make her trips down South until the eve of the War Between the States. Once the Civil War began, Harriet, always desiring to be active in the cause of freedom for her people, joined the war effort as a scout and spy, supporting herself by cooking and cleaning for the Union troops.

After the war, Harriet took care of her mother and father, became involved in the suffrage movement, and started a home to take care of those who were old and sick. Between 1850 and 1860, Harriet Tubman guided out more than three hundred people including many of her family members.

She made nineteen trips in all and was very proud of the fact that she never once lost a single person under her care. “I never ran my train off the track,” she said, “and I never lost a passenger.” At the time Southern whites put a $12,000 price on her head—a fortune. By the start of the Civil War, she had brought more people out of slavery than any other American in history-black or white, male or female.

The power of Harriet Tubman’s life was rooted in her constant communion and intimacy with Jesus through the Holy Spirit as she fought against injustice and served others. As someone testified about her, “Her relations with the Deity were personal, even intimate, though respectful on her part. He always addressed her as Araminta…” Harriet Tubman lived a life of intimacy with Jesus and wisdom that empowered her to accomplish the tasks set before her.

Click Here For More Information…